Today we discussed Swift's GULLIVER'S TRAVELS. We were to have discussed Moliere's The Misanthrope but several in the class were missing due to Hallowe'en so we watched a BBC version of the play and we'll discuss it next week instead. Stephen left us with an intriguing thought which was to consider Celimene's perspective as a young widow at 20 or so, and how she is fighting and manipulating to retain her independence.

GULLIVER

What were the objects of Swift's satire in each voyage?

Lilliput - English and Irish society; religion (transubstantiation and the Big-Endians and Little-Endians) - getting into the modern times by 17th c. Aristotelian idea of the world is being disproved in Western Europe (Swift, Moliere and Montaigne - didn't defend the old but not embracing the new)

Questioning: Given that we have to change - is this the way to go?

Actual body and blood of Christ (transubstantiation) vs representative - Medieval debate and became a critical issue during the Protestant Reformation.

This time period was a tipping point for the culture - Western civilization ended up going towards Sciences and power politics, and we saw the decline of religion (in Western world).

Risky at that time to question - could be tried and executed for treason, for heresy

These days (20th c.) we use science fiction as satire since there aren't any undiscovered corners of Earth (other than the occasional use of lost Amazonian tribe scenarios in fiction).

Swift was mainly going after politicians, also hereditary aristocracy and high clergy

Starts with Gulliver as giant (self-satisfied), progresses to small (misanthropic), assaulted by nature and by the end Nature (Horse) is his master - at the time, much thinking about what was Nature, what was man's place in Nature.

Voyages of exploration especially by sea were the 18th c. version of Star Trek - going out into the unknown and finding new cultures.

Wednesday, October 31, 2012

Tuesday, October 30, 2012

Moliere's THE MISANTHROPE

Moliere, The Misanthrope, Trans. Henri van Laun, Dover Thrift Editions, Mineola, 1992

Moliere (Jean Baptiste Poquelin, 1622-1673) was born in Paris and educated by the Jesuits. He formed a touring company and toured around France before returning to Paris and becoming the Troupe du Roi.

This is a very brief play. I found it humorous (though not in a rip-roaring way more a snicker at the foibles of society and the pompous and severe).

Alceste would be fun to play as an actor. He has a good line right off the bat:

pg 2 "To esteem everyone is to esteem no one"

He is an odd mix of reason and passion - he has strong ideals and has no patience for the hypocrisies of society, faking warmth and friendship. But he is undone by his inexplicable passion for Celimene and lets his passion overcome his common sense and his principles.

There are two characters who play sidekick roles and seem less strong than Alceste or Celimene but at the end they seem to be the ones who come out of it all alright - no lawsuits, in love with each other and happy about it, not prey to the heights of passion nor the depths of despair. They combine Reason with morals: Philinte & Eliante.

For someone who has Reason but seems without morals, Celimene seems quite cold-blooded and cruel.

Both Alceste & Oronte seem quite passionate. Alceste seems to have morals, I'm not sure about Oronte.

The other characters seem to be foolish, with not much reason and not even much passion (the two Marquis and Arsinoe) but their passion is probably real.

It will be interesting to discuss this play as I feel that I'm missing a few layers.

Alceste would be fun to play as an actor. He has a good line right off the bat:

pg 2 "To esteem everyone is to esteem no one"

He is an odd mix of reason and passion - he has strong ideals and has no patience for the hypocrisies of society, faking warmth and friendship. But he is undone by his inexplicable passion for Celimene and lets his passion overcome his common sense and his principles.

There are two characters who play sidekick roles and seem less strong than Alceste or Celimene but at the end they seem to be the ones who come out of it all alright - no lawsuits, in love with each other and happy about it, not prey to the heights of passion nor the depths of despair. They combine Reason with morals: Philinte & Eliante.

For someone who has Reason but seems without morals, Celimene seems quite cold-blooded and cruel.

Both Alceste & Oronte seem quite passionate. Alceste seems to have morals, I'm not sure about Oronte.

The other characters seem to be foolish, with not much reason and not even much passion (the two Marquis and Arsinoe) but their passion is probably real.

It will be interesting to discuss this play as I feel that I'm missing a few layers.

Jonathan Swift's GULLIVER'S TRAVELS

Swift, Jonathan, Gulliver's Travels, Oxford University Press, New York, 2005

I have vague memories of reading a kid's version of Gulliver's Travels - and an even vaguer memory of a comic book. I don't remember anything political or controversial - just the concept of travelling to unknown lands and finding very different worlds.

Swift targets not only government, royalty & aristocracy but also lampoons anyone who sets themself up as important.

pg 112 - "...how vain an Attempt it is for a Man to endeavour doing himself Honour among those who are out of all Degree of Equality or Comparison with him. And yet I have seen the Moral of my own behaviour very frequent in England since my return; where a contemptible little Varlet, without the least Title to Birth, Person, Wit, or common Sense, shall presume to look with Importance, and put himself upon a foot with the greatest Persons of the Kingdom."

Interesting to see how his use of various words and phrases differs from today's usage. Some of the words are commonly used in many english novels i.e. "nice" meaning delicate or skillful. But others are different from how we would say something today such as "artificially" for skillfully (pg 114), "seasonable Supply" meaning "opportune replacement (pg 114), Also different spellings (croud for crowd, consort for concert, pumpion for pumpkin, jobbs for jobs, chuse for choose, fole for foal

In Lilliput, Swift seems to want to depress any and all pretensions. In Brobdingnag he seems to focus in more on England and the monarchy. I'm not sure how much to make of examples showing a seeming difference social or moral niceties in Lilliput vs. in Brobdingnag. On pg 114 Gulliver won't sit on a chair made of the Queen's [shed] hair (out of respect) but in Lilliput he urinated on the Queen's quarters to put out a fire.

pg 116 Swift notes that reason is not proportional to size - is this a comment on human vs animal or more about various stations in life?

"That, Reason did to extend itself with the Bulk of the Body: On the contrary, we observed in our Country, that the tallest, Persons were usually least provided with it."

Gulliver speaks in favour of 3 kingdoms (and not union of England and Scotland in 1707 and [ironically on Swift's part] about extraordinary care taken in education of the aristocracy and the role of House of Peers.

One of the end notes speaks about Swift's view of English House of Lords being the final court of appeal for Ireland (rather than Irish House of Lords). In a letter Swift writes "...the Question is whether People ought to be Slaves or no" pg 311 Given what seemed to be Swift's opinion about the Irish Catholics, this seems a hypocritical question.

There is a long dialogue between Gulliver and the Brobdingnangian king about England: the hereditary nobility (pg 117) "Ornament and Bulwark of the Kingdom," comments about high clergy (Bishops), lawyers etc.

Irony mark

Swift uses a lot of irony. Irony is defined as a situation where:

"the surface meaning and the underlying meaning of what is said are not the same." Also, Eric Partridge, in Usage and Abusage, writes that "Irony consists in stating the contrary of what is meant."

The use of irony may require the concept of a double audience. Fowler's A Dictionary of Modern English Usage says:

Some examples of use of IRONY in Swift pg 116, 117, 118

pg 120 - supports freedom of thought - should be defended

pg 120 irony - "clearly proved that Ignorance , Idleness, and Vice are the proper Ingredients for qualifying a Legislator. That Laws are best explained, interpreted, and applied by those whose interest and Abilities lie in perverting, confounding, and eluding them."

pg 122 - "But great Allowances should be given to a King who lives wholly secluded from the rest of the World, and must therefore be altogether unacquainted with the Manners and Customs that most prevail in other Nations: The want of which Knowledge will ever produce many Prejudices, and a certain Narrowness of Thinking; from which we and the politer Countries of Europe are wholly exempted."

The Brobdingnagian King is horrified at the thought of weapons of war and destruction (gunpowder and firearms) and rejects Gulliver's offer to put these weapons in his hands to conquer all around him. Gulliver comments (pg124) "A strange Effect of narrow Principles and short Views!"

They have an interesting rule or law, (in the interests of the current Plain Language movement):

"No Law of that Country must exceed in Words the Number of Letters in their Alphabet."

Gulliver mentions "Politicks as Science " which seems to allude to Machiavelli and his findings.

In his voyage to Houyhnhnms Land, Gulliver comments about a Captain (pg 207), " a little too positive in his Opinions, which was the Cause of his Destruction, as it hath been of several others."

Here Gulliver seems more cynical and disenchanted with European society. He is horrified at the Yahoos' bestiality. At the same time he is quite enamoured of the Houyhnhnms ' reason and their just, orderly life - though there is social stratification there. pg 212 "I plainly observed that their Language expressed the Passions very well..."

Their reason is described in the end notes as (pg 345) "cognitive rather than ratiocinative."

For the Houyhnhnms, lying is difficult (pg 223) "Doubting or not believing are so little known in this country that the Inhabitants cannot tell how to behave themselves under such Circumstances."

"The Use of Speech was to make us understand one another, and to receive Information of Facts."

The Houyhnhnms are contrasted with the animalistic Yahoos, with the comment that (pg 225) "reason will in Time always prevail against Brutal Strength."

They also speak about (pg 229) things indifferent (pg 347) which reminds me of a term used by either the Epicureans or the Stoics for unimportant things - I'll have to go back Lucretius or Marcus Aurelius and find the reference.

Swift has a long description of stupid reasons for going to war, which we could pull out anytime in the current century.

He also gets into quite a diatribe against the Law and lawyers, proving black is white according how they are paid. He also has a very apt comment on the length of legal proceedings, on pg 232.

He discusses reason and brutality; Nature and reason, the stoics; Reason as common law - and notes that reason is prevented by self-love and by the passions.

The castigations continue: on pg 239, against aristocracy, inbreeding, cuckholdry, hybrid vigour.

Swift ironically lists the various uses of reason by Mankind, and the corruptions on pg 241.

"[...] he looked upon us as a Sort of Animal to whose Share, by what Accident he could not conjecture, some small Pittance of Reason had fallen, whereof we made no other Use than by its Assistance to aggravate our natural Corruptions, and to acquire new ones which Nature had not given us. That we disarmed our selves of the few Abilities she had bestowed; had been very successful in multiplying our original Wants, and seemed to spend our whole Lives in vain Endeavours to supply them by our own Inventions."

On pg 242 he turns his lens on civil war "for if you throw among five Yahoos as much food as would be sufficient for 50, they will, instead of eating peaceably, fall together by the Ears, each single one impatient to have it all to it self." "then would ensue such a Battle [...] with terrible Wounds made by their Claws on both sides." He then goes on to talk about the Yahoos coveting and fighting over coloured stones.

It was an interesting book. I wish I remembered more about what I got out of it as a child, whether the irony came through. It's a bit dated as a political instrument now since this type of commentary does not typically have to be hidden and disguised (in truly democratic countries).

I have vague memories of reading a kid's version of Gulliver's Travels - and an even vaguer memory of a comic book. I don't remember anything political or controversial - just the concept of travelling to unknown lands and finding very different worlds.

Swift targets not only government, royalty & aristocracy but also lampoons anyone who sets themself up as important.

pg 112 - "...how vain an Attempt it is for a Man to endeavour doing himself Honour among those who are out of all Degree of Equality or Comparison with him. And yet I have seen the Moral of my own behaviour very frequent in England since my return; where a contemptible little Varlet, without the least Title to Birth, Person, Wit, or common Sense, shall presume to look with Importance, and put himself upon a foot with the greatest Persons of the Kingdom."

Interesting to see how his use of various words and phrases differs from today's usage. Some of the words are commonly used in many english novels i.e. "nice" meaning delicate or skillful. But others are different from how we would say something today such as "artificially" for skillfully (pg 114), "seasonable Supply" meaning "opportune replacement (pg 114), Also different spellings (croud for crowd, consort for concert, pumpion for pumpkin, jobbs for jobs, chuse for choose, fole for foal

In Lilliput, Swift seems to want to depress any and all pretensions. In Brobdingnag he seems to focus in more on England and the monarchy. I'm not sure how much to make of examples showing a seeming difference social or moral niceties in Lilliput vs. in Brobdingnag. On pg 114 Gulliver won't sit on a chair made of the Queen's [shed] hair (out of respect) but in Lilliput he urinated on the Queen's quarters to put out a fire.

pg 116 Swift notes that reason is not proportional to size - is this a comment on human vs animal or more about various stations in life?

"That, Reason did to extend itself with the Bulk of the Body: On the contrary, we observed in our Country, that the tallest, Persons were usually least provided with it."

Gulliver speaks in favour of 3 kingdoms (and not union of England and Scotland in 1707 and [ironically on Swift's part] about extraordinary care taken in education of the aristocracy and the role of House of Peers.

One of the end notes speaks about Swift's view of English House of Lords being the final court of appeal for Ireland (rather than Irish House of Lords). In a letter Swift writes "...the Question is whether People ought to be Slaves or no" pg 311 Given what seemed to be Swift's opinion about the Irish Catholics, this seems a hypocritical question.

There is a long dialogue between Gulliver and the Brobdingnangian king about England: the hereditary nobility (pg 117) "Ornament and Bulwark of the Kingdom," comments about high clergy (Bishops), lawyers etc.

Irony mark

The irony mark or irony point (؟) (French: point d’ironie) is a punctuation mark proposed by the French poet Alcanter de Brahm (alias Marcel Bernhardt) at the end of the 19th century used to indicate that a sentence should be understood at a second level (irony, sarcasm, etc.). It is illustrated by a small, elevated, backward-facing question mark.[3]

It was in turn taken by Hervé Bazin in his book Plumons l’Oiseau ("Let's pluck the bird," 1966), where the author however used another (ψ-like) shape.[6] In doing this, the author proposed five other innovative punctuation marks: the "doubt point" ( ), "certitude point" (

), "certitude point" ( ), "acclamation point" (

), "acclamation point" ( ), "authority point" (

), "authority point" ( ), and "love point" (

), and "love point" ( ).[7]

).[7]

Swift uses a lot of irony. Irony is defined as a situation where:

"the surface meaning and the underlying meaning of what is said are not the same." Also, Eric Partridge, in Usage and Abusage, writes that "Irony consists in stating the contrary of what is meant."

The use of irony may require the concept of a double audience. Fowler's A Dictionary of Modern English Usage says:

Irony is a form of utterance that postulates a double audience, consisting of one party that hearing shall hear & shall not understand, & another party that, when more is meant than meets the ear, is aware both of that more & of the outsiders' incomprehension.

Some examples of use of IRONY in Swift pg 116, 117, 118

pg 120 - supports freedom of thought - should be defended

pg 120 irony - "clearly proved that Ignorance , Idleness, and Vice are the proper Ingredients for qualifying a Legislator. That Laws are best explained, interpreted, and applied by those whose interest and Abilities lie in perverting, confounding, and eluding them."

pg 122 - "But great Allowances should be given to a King who lives wholly secluded from the rest of the World, and must therefore be altogether unacquainted with the Manners and Customs that most prevail in other Nations: The want of which Knowledge will ever produce many Prejudices, and a certain Narrowness of Thinking; from which we and the politer Countries of Europe are wholly exempted."

The Brobdingnagian King is horrified at the thought of weapons of war and destruction (gunpowder and firearms) and rejects Gulliver's offer to put these weapons in his hands to conquer all around him. Gulliver comments (pg124) "A strange Effect of narrow Principles and short Views!"

They have an interesting rule or law, (in the interests of the current Plain Language movement):

"No Law of that Country must exceed in Words the Number of Letters in their Alphabet."

Gulliver mentions "Politicks as Science " which seems to allude to Machiavelli and his findings.

In his voyage to Houyhnhnms Land, Gulliver comments about a Captain (pg 207), " a little too positive in his Opinions, which was the Cause of his Destruction, as it hath been of several others."

Here Gulliver seems more cynical and disenchanted with European society. He is horrified at the Yahoos' bestiality. At the same time he is quite enamoured of the Houyhnhnms ' reason and their just, orderly life - though there is social stratification there. pg 212 "I plainly observed that their Language expressed the Passions very well..."

Their reason is described in the end notes as (pg 345) "cognitive rather than ratiocinative."

For the Houyhnhnms, lying is difficult (pg 223) "Doubting or not believing are so little known in this country that the Inhabitants cannot tell how to behave themselves under such Circumstances."

"The Use of Speech was to make us understand one another, and to receive Information of Facts."

The Houyhnhnms are contrasted with the animalistic Yahoos, with the comment that (pg 225) "reason will in Time always prevail against Brutal Strength."

They also speak about (pg 229) things indifferent (pg 347) which reminds me of a term used by either the Epicureans or the Stoics for unimportant things - I'll have to go back Lucretius or Marcus Aurelius and find the reference.

Swift has a long description of stupid reasons for going to war, which we could pull out anytime in the current century.

He also gets into quite a diatribe against the Law and lawyers, proving black is white according how they are paid. He also has a very apt comment on the length of legal proceedings, on pg 232.

He discusses reason and brutality; Nature and reason, the stoics; Reason as common law - and notes that reason is prevented by self-love and by the passions.

The castigations continue: on pg 239, against aristocracy, inbreeding, cuckholdry, hybrid vigour.

Swift ironically lists the various uses of reason by Mankind, and the corruptions on pg 241.

"[...] he looked upon us as a Sort of Animal to whose Share, by what Accident he could not conjecture, some small Pittance of Reason had fallen, whereof we made no other Use than by its Assistance to aggravate our natural Corruptions, and to acquire new ones which Nature had not given us. That we disarmed our selves of the few Abilities she had bestowed; had been very successful in multiplying our original Wants, and seemed to spend our whole Lives in vain Endeavours to supply them by our own Inventions."

On pg 242 he turns his lens on civil war "for if you throw among five Yahoos as much food as would be sufficient for 50, they will, instead of eating peaceably, fall together by the Ears, each single one impatient to have it all to it self." "then would ensue such a Battle [...] with terrible Wounds made by their Claws on both sides." He then goes on to talk about the Yahoos coveting and fighting over coloured stones.

It was an interesting book. I wish I remembered more about what I got out of it as a child, whether the irony came through. It's a bit dated as a political instrument now since this type of commentary does not typically have to be hidden and disguised (in truly democratic countries).

Sunday, October 28, 2012

DISCUSSION: De Las Casas and Montaigne

Another guest lecturer tonight, Dr. Ellie Stebner leading our discussion of Montaigne.

We started with De Las Casas. I'd sent out the following questions for consideration:

Use of Sarcasm

· “This is yet another example of the great deeds of these benighted Spaniards and of the ways in which they bring lustre and honour to the name of the Lord” (pg 67).

· “As they were subject to more and yet more injustice by Spaniards passing through the region on their way to tyrannize other provinces (or, as they would put it, ‘explore’ them)” (pg. 69)

· Noting that Spaniards buying slaves would say to the devil with any sick or elderly people, he comments “Reactions like these serve to give some idea of what the Spanish think of the native people, and how closely they obey that commandment to love one’s neighbor that underpins the Law and the books of the Prophets.” (pg 93)

We had a good discussion in class. When we were speaking about the "Lord of the Flies" aspect, whether all humans would be capable of such "inhumane" actions given the right set of circumstances, it seemed that the majority of the class felt that this capability lies within all of us. Several people cited various 20th and 21st century experiments where people very quickly were induced to behave very unjustly to colleagues or fellow students by fairly mild psychological or situational manipulations. Stephen maintained his view that this "inhumanity", brutality and lack of compassion or empathy is not an innate human trait.

We didn't get into a discussion of slavery - something practiced by the Spaniards against the natives as well as against imported African slaves but also something practiced by many of the indigenous tribes and nations themselves. I was interested in this topic because slavery is such a contentious topic in North America but it is far from being a practice used only by Europeans. They did manage to utilize slavery on a much broader scale than most other contemporary nations/cultures (though historically I would imagine the Mongols, Romans and the Ottomans had slavery on a similar scale).

Regarding whether reason or passion was more persuasive or more motivating, I think it is the combination of the two that is most effective. And in fact, when we were discussing this the question came up of the definition of reason vs passion and Stephen remarked that we will likely find by the end of the year the two are inextricably intertwined.

MONTAIGNE

Dr. Stebner lead a good, though brief discussion about Montaigne. I found this a challenging text, especially having to read it as quickly as I did due to the extra class and extra books this week. Ellie gave a wonderful intro and summary of Montaigne - I was scribbling hard to get much of it down as it seems to make so much of what I had read clear.

QUESTIONS

1. 1st modern - this title is usually given to Rousseau, Descartes – but truly modern person is not a sceptic but is a believer in Reason. Post-modern writer Derrida opens with Montaigne

Truth is what you want to make it, what is plausible

Scepticism is a healthy starting point, for Montaigne it’s also an ending point. Doesn’t preclude accepting something - his skepticism is an ethical stance – ‘virtue is not happiness’ – difficult to be a sceptic about everything

Byron says it’s easier to accept things than to question everything -

Sceptic lifestyle – difficult to put into practice – not enough time to take everything down to the foundations

Bruce – Scottish train with mathematician, biologist and philosopher - black sheep (philosopher says "all the sheep in Scotland are black", biologist says "no, there is one black sheep in Scotland", mathematician says "no, there is at least one sheep in Scotland is black on one side")

Be clear about the limits of your knowledge

We have to start somewhere or else we are paralyzed – where you start is often a place where you have to make an assumption.

Jonas – loved the book – are ignorant people really happier than learned people?

Abilio felt that Montaigne used imagination in the reverse way, to deconstruct everything rather to to create things.

Stephen said Montaigne uses footnotes to justify things in a way we don’t do now – he relied on masses of ancient thinkers and quotes to justify his ideas – this soon fell out of favour – last of the ancient scholars – Montaigne respects those sources -

Naomi – liked where Montaigne says he took a position opposite to his opinion and argued it just for fun - and convinced himself and ended up changing his opinion.

2 . Those who don’t know are happier than those who know – maybe we can’t attain freedom because we won’t know it when we have it – those who don’t ponder happiness are happier – though there is much danger of romanticizing the “simpler” life. Utopian ideal is not to return to a simple subsistence lifestyle but to want to transcend this to a better life, simpler but through a complex societal evolution that takes away or manages our daily needs and dangers so that we can have a simple happy life (Bacon's New Atlantis?).

3 . Montaigne wants to free himself from Doctors – be free from reliance on others?

4 . How do we live?

5 . What do we do with what we don’t know?

6 . Are our senses reliable?

7 . Did he himself reject dogma – can only take to a certain point then need something external to provide 1st principles

A related book to read: Saul Frampton – When I’m playing with My Cat . . .

We started with De Las Casas. I'd sent out the following questions for consideration:

QUESTIONS

- 1. De Las Casas devoted most of his adult life to travelling around the “Indies”, and back & forth to Spain, advocating for reform in how the Spaniards were governing in the Americas (especially with regards to their abuse of the indigenous peoples). Was De Las Casas motivated by reason or by passion?

- 2. De Las Casas wrote a very disturbing text, full of strong condemnation of Spain. Was De Las Casas more motivated by compassion for the injustice and the suffering inflicted upon the indigenous people, or by fear of Divine Retribution being visited upon Spain for Spanish “sins against the honour of God?”

- 3. In ‘A Short Account’ De Las Casas uses both reason and passion to support his plea for ‘legal and institutional reform’ in the Americas. Consider examples of each type of argument. Which approach was the most effective?

- 4. De Las Casas speaks about the greed of the Conquistadors as a root cause of the abuses. He writes, “Spaniards […] would attack and rob the Devil himself if he had gold about his person.” He also quotes Hatuey, a ‘cacique’ who fled the Spanish slaughter on Hispaniola, only to find Cuba similarly overrun by the Conquistadors. Hatuey told his people that the Christians “have a God whom they worship and adore, and it is in order to get that God from us so that they can worship Him that they conquer and kill us.” Pointing to a basket of gold jewellery Hatuey said “Here is the God of the Christians.” De Las Casas makes mention many times that the local people were neither ambitious nor greedy. Is greed a particularly European trait, a Catholic or Christian trait? Was it purely greed that impelled the Spaniards to behave so abhorrently in the Americas or did the distance from home and society allow human qualities to come out that are waiting to manifest themselves within each of us? Were there any other factors that likely contributed to the scale of the atrocities?

- 5. One of the abhorrent aspects of the ‘Spanish Conquest’ in the Americas was the enslavement of the indigenous peoples and the resulting slave trade. In his chapter on Guatemala, Las Casas describes an episode where de Alvarado laid waste to a region because they didn’t have the gold the Spaniards wanted. They enslaved the survivors and De Las Casas writes “when they pressed for further slaves to be handed over by way of tribute, the natives gave up their own sons and daughters, as they had no further slaves to surrender.” (pg 61) Was the enslavement of Amerindians by the Spaniards morally any different than the enslavement practiced by the Amerindians themselves?

- 6. De Las Casas uses very strong and vivid language to describe the cruelty and perfidy of the Spaniards. In contrast he infantilizes the local peoples, consistently describing them as “gentle lambs”, “open and innocent”, “submissive”, “obedient”, “without malice or guile”, “particularly receptive to learning”. Was this paternalistic perspective his true view of the Amerindian people or merely a rhetorical device to simplify and strengthen his pleas to the Spanish Crown for reforms in the Americas?

- 7. De Las Casas’ report of the Conquistadors’ actions in the Americas reads like a textbook description of a Machiavellian campaign. Consider the number of Machiavelli’s principles that were employed in the ‘Spanish Conquest’. Below are 4 examples:

a. Slaughter the leaders

b. Use fear to control the people

i. “It is much more secure to be feared than to be loved”

c. Lie and deceive to get what you want

i. “Men are so simple and yield so readily to the desires of the moment that he who will trick will always find another who will suffer to be tricked”.

ii. “The promise given was a necessity of the past: the word broken is a necessity of the present”.

d. Act severely and strongly

i. If an injury has to be done to a man it should be so severe that his vengeance need not be feared. ii. Whoever conquers a free town and does not demolish it commits a great error and may expect to be ruined himself.

iii. Men ought either to be indulged or utterly destroyed, for if you merely offend them they take vengeance, but if you injure them greatly they are unable to retaliate, so that the injury done to a man ought to be such that vengeance cannot be feared.

I was also aware of De Las Casas use of sarcasm to make his point or as commentary on the baseness of the actions he is writing about.

Use of Sarcasm

· “This is yet another example of the great deeds of these benighted Spaniards and of the ways in which they bring lustre and honour to the name of the Lord” (pg 67).

· “As they were subject to more and yet more injustice by Spaniards passing through the region on their way to tyrannize other provinces (or, as they would put it, ‘explore’ them)” (pg. 69)

· Noting that Spaniards buying slaves would say to the devil with any sick or elderly people, he comments “Reactions like these serve to give some idea of what the Spanish think of the native people, and how closely they obey that commandment to love one’s neighbor that underpins the Law and the books of the Prophets.” (pg 93)

- Humans find difficult to distinguish between true and false. How do we even know?

- Passions/minds deceive us

- All previous sages limited and disagreed with one another

- No way to get beyond limitness of human limits

- We think we are superior to all other creatures yet we can’t even understand other creatures

- Regard other humans as barbarians

- No understanding of nature yet alone what is within us

- Constrained by an order we don’t or can’t understand

- All must come from an outside source – for Montaigne, this is God

- Problem for Montaigne that Luther and Calvin base their arguments on reason

- What is reason or conscience?

- Christian beliefs can’t be based on reason

- Ignorance and violence of human reason – results in vanity and foolishness

- Humans need to get beyond ourselves

- Acknowledge God as incomprehensible, not limited by time or impermanence

- We are all impermanent – this is the bottom line for Montaigne

- We are just human – yet become stuffed up and self-centered

- We don’t even know how to be happy, ignorant people often happier than learned

- We don’t even know how to think, know nothing about our bodies let alone spirit

- Reason doesn’t make us content, doesn’t make us ethical or moral

Montaigne wants to be practical – if there is a purpose for reason it is that it calls us to freedom – freedom from doctrinal ideological thinking, can we

imagine things being other, can we imagine a world beyond what we know?

Our goal is to question everything not only what we see but

what we feel, not only what we feel but what we taste – we have to recognize

what we taste but realize that it’s not what everyone tastes.

Montaigne's strengths: Style, earthiness, ability to point to smallest of things

He was the father of the essay – from the French word essayer “to make an attempt”, attempt to

understand something, to weigh something

Mentioned a Sarah Bakewell book – the whole point of Montaigne is how to

live – The book sets out 20 tips on how to live

- Don’t worry about death

- Pay attention

- Be born

- Read a lot but forget

- Survive love and loss

- Use little tricks

- Question everything

- Have a Private room (a Room of One's Own?)

- Be convivial

- Wake from sleep of habit

- Live temperately

- Guard your humanity

- Do something no one else has done before

- See the world

- Do a good job but not too good

- Reflect on everything and regret nothing

- Give up control

- Be ordinary and imperfect

- Let life be its own answer

Says Montaigne is the 1st truly modern individual

1. 1st modern - this title is usually given to Rousseau, Descartes – but truly modern person is not a sceptic but is a believer in Reason. Post-modern writer Derrida opens with Montaigne

Truth is what you want to make it, what is plausible

Scepticism is a healthy starting point, for Montaigne it’s also an ending point. Doesn’t preclude accepting something - his skepticism is an ethical stance – ‘virtue is not happiness’ – difficult to be a sceptic about everything

Byron says it’s easier to accept things than to question everything -

Sceptic lifestyle – difficult to put into practice – not enough time to take everything down to the foundations

Bruce – Scottish train with mathematician, biologist and philosopher - black sheep (philosopher says "all the sheep in Scotland are black", biologist says "no, there is one black sheep in Scotland", mathematician says "no, there is at least one sheep in Scotland is black on one side")

Be clear about the limits of your knowledge

We have to start somewhere or else we are paralyzed – where you start is often a place where you have to make an assumption.

Jonas – loved the book – are ignorant people really happier than learned people?

Abilio felt that Montaigne used imagination in the reverse way, to deconstruct everything rather to to create things.

Stephen said Montaigne uses footnotes to justify things in a way we don’t do now – he relied on masses of ancient thinkers and quotes to justify his ideas – this soon fell out of favour – last of the ancient scholars – Montaigne respects those sources -

Naomi – liked where Montaigne says he took a position opposite to his opinion and argued it just for fun - and convinced himself and ended up changing his opinion.

2 . Those who don’t know are happier than those who know – maybe we can’t attain freedom because we won’t know it when we have it – those who don’t ponder happiness are happier – though there is much danger of romanticizing the “simpler” life. Utopian ideal is not to return to a simple subsistence lifestyle but to want to transcend this to a better life, simpler but through a complex societal evolution that takes away or manages our daily needs and dangers so that we can have a simple happy life (Bacon's New Atlantis?).

3 . Montaigne wants to free himself from Doctors – be free from reliance on others?

4 . How do we live?

5 . What do we do with what we don’t know?

6 . Are our senses reliable?

7 . Did he himself reject dogma – can only take to a certain point then need something external to provide 1st principles

A related book to read: Saul Frampton – When I’m playing with My Cat . . .

Saturday, October 27, 2012

Montaigne's Apology for Raymond Sebond

de Montaigne, Michel, Apology for Raymond Sebond, Transl. Roger Ariew & Marjorie Grene, Hackett, 2003, Indianapolis

Michel de Montaigne was born in 1533, into an aristocratic family at the chateau de Montaigne near Bordeaux. His mother was from a wealthy, originally Iberian, Jewish family. The children were all raised Catholic though some of Montaigne's siblings later became Protestant. His father was given a book by Raymond Sebond titled Natural Theology. Montaigne mentions that "the novelties of Luther were beginning to gain favour and to shake our traditional belief in many places." Sebond was a Spanish medical doctor practicing in Toulouse two hundred years earlier and his book was a defense of Catholicism against atheists. Montaigne translated the book into French for his father and it was published. Montaigne comments that he felt he should write the Apology (pg 2) "Since many people take pleasure in reading him - and especially the ladies, to whom we have to give particular assistance [...]"

FIRST OBJECTION AGAINST SEBOND, AND MONTAIGNE'S REPLY

Montaigne felt that radical scepticism of the Pyrrhonian variety is the proper intellectual attitude. Question everything. I liked the motto of the epechistes "I hold back" (meaning I withhold judgement) Good motto to have (and one Marcus Aurelius took very much to heart).

It is thought that all our seeming knowledge arises from our 5 senses.

Montaigne felt that belief comes from enlightenment from God. He thought that if this were not the case, then all the ancient wise people "would not have failed to arrive at that knowledge in their reasoning." pg 3 He is not blind to the many issues associated with religion including Catholicism and he discusses them in his book.

pg 5 "God owes his extraordinary aid to faith and religion, not to our passions.."

pg 5 "People are the leaders here and make use of religion. It ought to be quite the contrary."

pg 6 " We burn people who say that truth must suffer the yoke of our necessity."

pg 6 " I see clearly now that we willingly assign to devotion only the religious duties that flatter our passions."

pg. 6 "There is no hostility so extreme as that of the Christian. Our zeal works marvels when it seconds our inclination towards hatred, cruelty, ambition, greed, slander, and rebellion. On the other hand, it neither walks nor flies toward goodness, benevolence, temperance, if some rare complexion does not miraculously predispose it to them." "Our religion is meant to eradicate vices; it covers them, nourishes them, and encourages them."

Montaigne quotes Lucretius and Diogenes as he notes that if we truly believed in the blessings of heaven then why are we afraid of death, something I've always wondered about when being educated about Heaven or preached to about heaven.

He writes about people believing in religion through fear and those who find religion only when they are at risk of dying, in mortal terror. "A nice faith that believes what it believes only because it lacks the courage to disbelieve it." pg 8

In his 1st apology, Montaigne goes on to say that it's not credible that God has not left his mark somewhere in the world. He says that Sebond "shows us how there is no part of the world that disclaims its maker." pg 9 He ends by quoting Horace saying "If you have something better, produce it, or accept our rule."

SECOND OBJECTION AGAINST SEBOND, AND MONTAIGNE'S REPLY

In his reply to peoples' 2nd objection to Sebond, Montaigne says that his approach will be to "crush and trample underfoot human vanity and pride; to make them feel the inanity, the vanity and nothingness of man; to snatch from their hands the miserable weapons of their reason; to make them bow their heads and bite the dust beneath the authority and reverence of divine majesty." pg 11

He quotes many philosophers (Herodotus, the apostles Peter and James, Plato - he LOVES to quote) but to me they are just statements not proof and certainly not compelling. He also quotes St. Augustine who railed against the injustice of denying the truth of something on the basis that our reason has not been up to the challenge of proving it. This has more power for me but it still doesn't make articles of faith true (which I realize is somewhat of an oxymoronic statement on my part but makes a bit more sense if you are an unbeliever).

1. THE VANITY OF MAN'S KNOWLEDGE WITHOUT GOD

Montaigne goes on to examine man if there was no God and refers to man's dominion over everything asking "Is it possible to imagine anything so ridiculous as that this wretched and cowardly creature, who is not even master of himself, exposed to threats from all things, should call himself master and emperor of the universe when he lacks the power to understand its least part, let alone to command it?" (pg 12) Here is where Montaigne would have lost me had we been arguing this because I don't believe (nor do I think the majority believe in this day and age) that 'man' has dominion over the universe - though I would be hard-pressed to prove this seeing what we are doing to the environment and our hubris in genetic engineering (not because we are treading on God's territory but because I do believe in the inevitable 'rightness' [though that's not the correct word] of natural selection much more than I believe in human understanding or wisdom).

Part of his argument revolves around the power of the celestial bodies, the heavens to regulate men's lives and it's difficult for me to follow this argument, not having any knowledge of the state of astrology or cosmology at the time. I know that it was an active area and can easily look up that Copernicus published his work in 1543 and Galileo didn't publish until 1642 but other than this vague awareness, I'm ignorant of what was being thought and discussed at the time. There is a governing aspect to how he seems to consider the celestial sphere that I don't understand.

He quotes Seneca, writing "Among other inconveniences of mortality Is the darkness of the understanding , not so much the need to make errors as the love of errors."

2. MAN IS NO BETTER THAN THE BEASTS

Montaigne speaks about man being stuck in the worst part of the universe and in the "worst condition of the 3 kinds of animals" (i.e.: aerial, aquatic and terrestrial). He calls man presumptuous for putting himself above other animals, separating himself from other animals. "By what comparison between them and us does he infer the stupidity he attributes to them?" He says "When I play with my cat, who knows if she is making more of a pastime of me than I of her?" This thought has been the basis of many a joke and Gary Larson Far Side cartoon. Very pertinently Montaigne asks about animals "The same defect that prevents communication between them and us, why is it not as much our fault as theirs?" (pg 15).

He notes that "we discover quite plainly that there is full and complete communication between them and they understand one another, not only within the same species, but also across different species," and quotes Lucretius "And the cattle lacking speech, and even the wild beasts, make themselves understood with different and varied cries according as they feel fear, pain, or joy." If Lucretius understood in the 1st or 2nd century BCE that animals feel fear and pain, and Montaigne in the 16th c. AD quotes this, how does Descartes consider that animals were mechanistic (as our class discussion last night seemed to say) and how were vivisectionists up until only a few decades ago able to claim that animals don't feel pain as humans do? Montaigne lists off various aspects in which animals exceed humans in their ability and knowledge of the natural world and he comments "[...] their brutal stupidity surpasses, in all circumstances, everything that our divine invention and our arts can do." Montaigne quotes Lucretius again saying "Everything develops according to its own character, and all keep the differences that the fixed laws of nature have established between them" (pg 22) but he doesn't [yet] give us his thoughts on the laws of nature and what they are, where they come from and are they fixed? Montaigne speaks about whether man alone has imagination, if "this unruliness in his thoughts, representing to himself what is, what is not, and what he wishes - the false and the true - this is an advantage that has been dearly bought, giving him little to boast about. For from it flows the principal source of the evils that beset him: sin, illness, irresolution, affliction, and despair." (pg 22).

Montaigne says - and I don't know where the support for this statement comes from - "It is more honourable, and closer to divinity, to be guided and required to act in an ordered way by a natural and inevitable condition, rather than to act in that way through a presumptuous and fortuitous freedom."

Montaigne refers to differences between how we treat animals and says we also treat people differently, then referring to treatment of servants and slaves. He comments that "yet animals are more high-minded, since no lion ever enslaved itself to another lion, nor a horse to another horse, for lack of courage." (pg 24). He has a great line that could apply to 'o how the mighty are fallen' or 'he puts his shoes on one at a time just like everyone else' but much more vivid: "The heart and life of a great and triumphant emperor are but the breakfast of a little worm." (pg 25).

One amazing bit of information in this text is when Montaigne is enumerating various ways in which animals seem to have powers of reason (not just good instincts). He refers to dogs which guide the blind and describes several observed instances asking "How could anyone have made that dog understand that it was its task to consider only the safety of its master and to neglect its own comfort in order to serve him? And how did it know that a certain road would be quite broad enough for it, but would not be so for a blind man? Can all this be understood without ratiocination and without thought?" (pg 26)

"It is one and the same nature that runs its course. If anyone had judged well enough of the present state, he could certainly infer from this both the whole of the future and the whole of the past." (pg 29).

Though Montaigne professes admiration for many of animals' qualities, his interpretation of some observations and stories is still quite anthropomorphic. He describes the story of the philosopher Thales' mule who stumbled while carrying a load of salt across the river. Realizing that its load was now lighter (because some of the salt has melted) the mule made it a practice to put its load under water. Montaigne describes this as malice and the mule as having malicious subtlety. It seems to be to be intelligence and figuring out a cause and effect relationship which is how we think animals primarily learn - admittedly a difficult cause and effect relationship because there would be a lag time between the action and the effect but research is currently being done showing some animals to be capable of episodic memory.

"As to war, which is the greatest and most solemn of human actions, I would like to know if we want to use it as an argument for some prerogative, or, on the contrary, as evidence of our imbecility and imperfection; as indeed our knowledge of how to defeat and slaughter one another, to ruin and destroy our own species, seems to have little attraction for the beats who do not have it." (pg 35)

"The souls of Emperors and of cobblers are cast in the same hold." (pg 38)

Montaigne mentions the ichneumon a couple of times. This is an african mongoose reputed to attack or control crocodiles by stealing and eating its eggs.

3. MAN'S KNOWLEDGE CANNOT MAKE HIM HAPPY

"If man were wise, he would fix the true price of each thing according to its greatest utility and fitness for his life." (pg 49)

"It is only humility and submission that can produce a good man." Montaigne says that man "must not be allowed o choose [his duty] according to his reasoning; others according to the imbecility and infinite variety of our arguments and opinions, we would finally forge for ourselves duties that would set us to eating one another..." (pg49). He adds that the 1st law God gave man was "a law of pure obedience". "[...] every sin arises from being opinionated." "The 1st temptation that came to human nature from the side of the devil, his 1st poison, was insinuated in us through the promises he made us of knowledge and awareness." "Man's plague is the belief that he has knowledge." (pg 50)

"That is why ignorance is so highly recommended by our religion as appropriate for belief and obedience."

Montaigne says that there is general agreement among philosophers that "the sovereign good consists in tranquility of soul and body."

Epictetus says that "man has nothing uniquely his own except the use of his opinions".

"We have to be made into animals to become wise and dazzled in order to be guided" (pg. 54)

He quotes Ecclesiastes 1:18 "In much wisdom there is much grief; and he who increases knowledge, increases travail and sorrow." (pg 57)

and Seneca "Does it please you? Bear it. Does it not please you? Get out of it however you can."

4. MAN'S KNOWLEDGE CANNOT MAKE HIM GOOD

"How can reason and intelligence, of which we make use in order to move from the obscure to the clear, [belong to God], seeing there is nothing obscure to God?" (pg 61)

Montaigne quotes Aristotle saying "He is capable neither of favour nor anger, since where such passions are, they are all weaknesses." (pg 61)

Montaigne "[...] Our faith is not our own acquisition; it is a pure gift of another's liberality."

saying that it's not through our reason or our intellect that we receive our religion.

5. MAN HAS NO KNOWLEDGE

In which Montaigne tries to answer whether man's search for knowledge over the centuries has enriched him or provided any "solid truth". The main benefit has been to recognize man's weakness.

"This largest part of what we know is the smallest part of the things we do not know." or "Even what we think we know is a piece, and a very small piece, of our ignorance." (pg 62)

Anyone seeking knowledge comes to one of 3 conclusions (pg 63):

"Anyone who imagines a perpetual confession of ignorance [...] will understand Pyrrhonism."

Montaigne is dismissive and even very negative about curiosity, about knowledge simply for knowledge's sake, mentioning Eudoxus who wanted some day to see the sun close up, even if "he would be at once burned up by it." He wants to acquire knowledge that will result, in the act of its acquisition, in his losing not only that knowledge but all his past and future knowledge. (pg 73).

He speaks about ancient philosophers having found an "occupation fitting for the natural curiosity in us." (pg 73)

On pg 76, Montaigne lists numerous thinkers and briefly sums up their beliefs or philosophy about God. He wonders why mankind has wanted to put human qualities and foibles onto God or their gods. "Man would have done better [...] to take to himself the conditions of divinity and to bring those conditions down here rather than to send up there his corruption and his wretchedness." (pg 79)

He speaks of Mohammed who "promises his people a carpeted paradise paved with gold and jewels, peopled with girls of great beauty, with wines and rare food, I see clearly that they are mockers who are catering to our stupidity to sweeten and attract us by these opinions and hopes, suited to our mortal appetite." This comment reminds me of visits I have had from Jehovah's Witnesses proseletyzing at my front door and thinking to convince me of the attractions of paradise by showing me cheap coloured cartoons of a version of the Garden of Eden, and telling me earnestly that this is where I could end up if I convert, pointing at the picture as if it was a glossy brochure from some time-share in Cancun.

"We want to enslave God to the vain and feeble appearance of our understanding, him who has made both us and our knowledge." (pg 85)

And he writes about the presumption of assuming that what God has wrought on Earth is the sum total of all his ideas and creations, "the sum of the whole of everything" as Lucretius said, VI 679-80

On pg 87 Montaigne gets into discussing hybrid and ambiguous forms between human and brute nature and describes "countries where men are born without heads, carrying their eyes and mouth on their chest" - I don't know where this came from - it reminds me of the section in Lucretius where he lists off all the fantabulous creatures in other parts of the world or in days past. I have a real problem with this section. Montaigne lists these bizarre forms of humans (with one eye on forehead, who are without a mouth and nourish themselves via odours etc) and then immediately goes on to say that if this is the case, "how many of our descriptions are false? Man can no longer laugh nor perchance be capable of reason and of society. The governance and the cause of our internal structure would be for the most part irrelevant." (pg 87). I don't see this as a logical conclusion to the presence (or possibility) of humans with different characteristics.

Montaigne writes about the practice for philosopher's of looking to the natural world for truth: "For to go according to nature, for us, is only to go according to our intelligence, insofar as we can follow ad insofar as we can see into it. What is beyond is monstrous and disordered." (pg 87). He mentions Euripides and quotes Stobaeus, "Who knows if what we call dying is not living, as living is dying." Montaigne says that our life is an infinitesimal mote in an infinity of time and writes that "death occupies all that is beyond and all that is before this moment and a good part of this moment as well." (pg 88).

He has a great paragraph (pg 88) briefly summarizing various philosophers' philosophies in one sentence. He has structured it well so that each summary either contradicts itself internally and/or contradicts the one before or after it, ending the list of course by saying "that even the one is not, and that there is nothing."

It's about how I'm feeling about all these ideas right now.

Montaigne then gets into a discussion about the limitations of language and again, this is something that is resonating with me right now because I am getting bogged down in definitions and in my lack of knowledge of scholastic terminology. We are reading 2 texts a week (and a couple of weeks 4 texts) and there isn't the time to do much research for context, background, much less the academic underpinnings.

Montaigne says "God cannot do everything; for God cannot kill himself when he wants to, which is the greatest privilege we have in our condition." "God has no power over the past except forgetfulness." (pg 89) "Our presumptuousness wants to pass divinity through our sieve." (pg 90)

He also writes about the presumptuousness of mankind to think that God cares more about or involves himself more in those things that are important to us. I've always felt this way about prayer, such as when you would hear about someone praying to win a football game or a big contract (why would God care and if He did care, why would he care more about you than about the other contenders), similarly when you would read about a devout king praying for success on the battlefield - why would God grant him success but allow defeat to the other side (assuming the same religion) or regardless of who wins, allow all the carnage and destruction of the battle itself? It never made sense to me (among oh so many other things admittedly). As Montaigne puts it His hand "extends to all things in the same way [...] our interest has nothing to do with it [...]" (pg 90)

I have trouble with the sentence "Nature wants like relations in like things." Says who? I agree that in the last century the concept of equilibrium seemed to hold true in many cases (physics, medicine, chemistry) with Newton's Law of Reciprocal Actions and the chemical reactions that occur constantly in our bodies to keep everything in equilibrium (acid-base, the colloid osmotic pressure within our circulation, the ion movements keeping our cells functioning etc). But where is Montaigne's proof of this statement. This is where my lack of context and knowledge about the state of scientific knowledge at the time becomes a major problem. There may have been some very strong proofs at the time about some theories of equilibrium - I don't know if Montaigne is basing his statement on something like that or on some empirical knowledge from observation of the natural world.

Montaigne considers that our souls are "free and separated from the body" when we sleep and they can divine or prognosticate and "see things they would not know how to see if they were mixed with bodies." (pg 91)

When speaking about how our imaginations can cause many/all of our problems, he quotes Lucan "What they have made, they fear" and Pliny "Who is unhappier than a man whom his fictions govern?" (pg 91).

He quotes Xenophanes who had said that animals probably create a God in their own image just as man does and then refers to a gosling saying "All parts of the universe concern me; the earth serves me for walking, the sun to give me light [...]; there is nothing that that vault looks on as favourably as it does me; I am the beloved of nature [...]" (pg. 94). He does not think much of how mankind has imbued their divinities with very base human traits and assumed the gods to be preoccupied with unimportant minutiae (having a god to cure horses and one to make grapes grow, one in charge of trade etc) - and Montaigne lists off reams of various gods that have been described over the ages.

Montaigne says (about mankind's ability to know anything) "I will leave here more ignorant of everything except my ignorance". (pg 98) He says that "the reason we scarcely doubt about things is that we never test common impressions" (pg 101) He goes through, again, various philosophers' ideas on how the universe is constructed ("the atoms of Epicurus, the fullness and void of Lucretius and Democritus, that water of Thales [...] the fire of Heraclitus") saying for Aristotle, why make a negative such as privation part of the cause and origin of everything. (pg 101). He warns about the practice of believing experts in other fields and relying on their principles or practices.

"Every human presupposition and pronouncement has as much authority as every other if it is only reason that makes the difference." (pg 102)

Montaigne goes on to discuss what human reason has taught us about itself and the soul. The soul is likely just one entity (not one for each body part) and "through its faculties, reasons, remembers, understands, judges, desires [...] - and it is located in the brain." (pg 108). He sets out various philosophers' ideas about the soul/mind - body connection and again quotes Lucretius: "The mind must be bodily in nature, since it suffers from the stroke of bodily weapons." (pg111). He says we own any truth to luck and circumstance and that our reason "does not have the power to take advantage of [truth]. All things produced by our own reasoning and competence, the true as much as the false, are subject to uncertainty and debate." (pg 115).

"lose ourselves in that vast and troubled sea of medical errors" (pg 118)

"Our mind is a wandering, dangerous, and foolhardy utensil; it is difficult to join to it any order or measure." (pg 120)

6. MAN'S CLAIMS TO KNOWLEDGE ARE DEFECTIVE

7. THE SENSES ARE INADEQUATE

8. CHANGING MAN CANNOT KNOW CHANGING OR UNCHANGING THINGS

"But what is it, then, that truly is." (pg 163)

"God, who alone is" (pg 163)

"He fills eternity with a single now" - the Penguin Edition

Michel de Montaigne was born in 1533, into an aristocratic family at the chateau de Montaigne near Bordeaux. His mother was from a wealthy, originally Iberian, Jewish family. The children were all raised Catholic though some of Montaigne's siblings later became Protestant. His father was given a book by Raymond Sebond titled Natural Theology. Montaigne mentions that "the novelties of Luther were beginning to gain favour and to shake our traditional belief in many places." Sebond was a Spanish medical doctor practicing in Toulouse two hundred years earlier and his book was a defense of Catholicism against atheists. Montaigne translated the book into French for his father and it was published. Montaigne comments that he felt he should write the Apology (pg 2) "Since many people take pleasure in reading him - and especially the ladies, to whom we have to give particular assistance [...]"

FIRST OBJECTION AGAINST SEBOND, AND MONTAIGNE'S REPLY

Montaigne felt that radical scepticism of the Pyrrhonian variety is the proper intellectual attitude. Question everything. I liked the motto of the epechistes "I hold back" (meaning I withhold judgement) Good motto to have (and one Marcus Aurelius took very much to heart).

It is thought that all our seeming knowledge arises from our 5 senses.

Montaigne felt that belief comes from enlightenment from God. He thought that if this were not the case, then all the ancient wise people "would not have failed to arrive at that knowledge in their reasoning." pg 3 He is not blind to the many issues associated with religion including Catholicism and he discusses them in his book.

pg 5 "God owes his extraordinary aid to faith and religion, not to our passions.."

pg 5 "People are the leaders here and make use of religion. It ought to be quite the contrary."

pg 6 " We burn people who say that truth must suffer the yoke of our necessity."

pg 6 " I see clearly now that we willingly assign to devotion only the religious duties that flatter our passions."

pg. 6 "There is no hostility so extreme as that of the Christian. Our zeal works marvels when it seconds our inclination towards hatred, cruelty, ambition, greed, slander, and rebellion. On the other hand, it neither walks nor flies toward goodness, benevolence, temperance, if some rare complexion does not miraculously predispose it to them." "Our religion is meant to eradicate vices; it covers them, nourishes them, and encourages them."

Montaigne quotes Lucretius and Diogenes as he notes that if we truly believed in the blessings of heaven then why are we afraid of death, something I've always wondered about when being educated about Heaven or preached to about heaven.

He writes about people believing in religion through fear and those who find religion only when they are at risk of dying, in mortal terror. "A nice faith that believes what it believes only because it lacks the courage to disbelieve it." pg 8

In his 1st apology, Montaigne goes on to say that it's not credible that God has not left his mark somewhere in the world. He says that Sebond "shows us how there is no part of the world that disclaims its maker." pg 9 He ends by quoting Horace saying "If you have something better, produce it, or accept our rule."

SECOND OBJECTION AGAINST SEBOND, AND MONTAIGNE'S REPLY

In his reply to peoples' 2nd objection to Sebond, Montaigne says that his approach will be to "crush and trample underfoot human vanity and pride; to make them feel the inanity, the vanity and nothingness of man; to snatch from their hands the miserable weapons of their reason; to make them bow their heads and bite the dust beneath the authority and reverence of divine majesty." pg 11

He quotes many philosophers (Herodotus, the apostles Peter and James, Plato - he LOVES to quote) but to me they are just statements not proof and certainly not compelling. He also quotes St. Augustine who railed against the injustice of denying the truth of something on the basis that our reason has not been up to the challenge of proving it. This has more power for me but it still doesn't make articles of faith true (which I realize is somewhat of an oxymoronic statement on my part but makes a bit more sense if you are an unbeliever).

1. THE VANITY OF MAN'S KNOWLEDGE WITHOUT GOD

Montaigne goes on to examine man if there was no God and refers to man's dominion over everything asking "Is it possible to imagine anything so ridiculous as that this wretched and cowardly creature, who is not even master of himself, exposed to threats from all things, should call himself master and emperor of the universe when he lacks the power to understand its least part, let alone to command it?" (pg 12) Here is where Montaigne would have lost me had we been arguing this because I don't believe (nor do I think the majority believe in this day and age) that 'man' has dominion over the universe - though I would be hard-pressed to prove this seeing what we are doing to the environment and our hubris in genetic engineering (not because we are treading on God's territory but because I do believe in the inevitable 'rightness' [though that's not the correct word] of natural selection much more than I believe in human understanding or wisdom).

Part of his argument revolves around the power of the celestial bodies, the heavens to regulate men's lives and it's difficult for me to follow this argument, not having any knowledge of the state of astrology or cosmology at the time. I know that it was an active area and can easily look up that Copernicus published his work in 1543 and Galileo didn't publish until 1642 but other than this vague awareness, I'm ignorant of what was being thought and discussed at the time. There is a governing aspect to how he seems to consider the celestial sphere that I don't understand.

He quotes Seneca, writing "Among other inconveniences of mortality Is the darkness of the understanding , not so much the need to make errors as the love of errors."

2. MAN IS NO BETTER THAN THE BEASTS

Montaigne speaks about man being stuck in the worst part of the universe and in the "worst condition of the 3 kinds of animals" (i.e.: aerial, aquatic and terrestrial). He calls man presumptuous for putting himself above other animals, separating himself from other animals. "By what comparison between them and us does he infer the stupidity he attributes to them?" He says "When I play with my cat, who knows if she is making more of a pastime of me than I of her?" This thought has been the basis of many a joke and Gary Larson Far Side cartoon. Very pertinently Montaigne asks about animals "The same defect that prevents communication between them and us, why is it not as much our fault as theirs?" (pg 15).

He notes that "we discover quite plainly that there is full and complete communication between them and they understand one another, not only within the same species, but also across different species," and quotes Lucretius "And the cattle lacking speech, and even the wild beasts, make themselves understood with different and varied cries according as they feel fear, pain, or joy." If Lucretius understood in the 1st or 2nd century BCE that animals feel fear and pain, and Montaigne in the 16th c. AD quotes this, how does Descartes consider that animals were mechanistic (as our class discussion last night seemed to say) and how were vivisectionists up until only a few decades ago able to claim that animals don't feel pain as humans do? Montaigne lists off various aspects in which animals exceed humans in their ability and knowledge of the natural world and he comments "[...] their brutal stupidity surpasses, in all circumstances, everything that our divine invention and our arts can do." Montaigne quotes Lucretius again saying "Everything develops according to its own character, and all keep the differences that the fixed laws of nature have established between them" (pg 22) but he doesn't [yet] give us his thoughts on the laws of nature and what they are, where they come from and are they fixed? Montaigne speaks about whether man alone has imagination, if "this unruliness in his thoughts, representing to himself what is, what is not, and what he wishes - the false and the true - this is an advantage that has been dearly bought, giving him little to boast about. For from it flows the principal source of the evils that beset him: sin, illness, irresolution, affliction, and despair." (pg 22).

Montaigne says - and I don't know where the support for this statement comes from - "It is more honourable, and closer to divinity, to be guided and required to act in an ordered way by a natural and inevitable condition, rather than to act in that way through a presumptuous and fortuitous freedom."

Montaigne refers to differences between how we treat animals and says we also treat people differently, then referring to treatment of servants and slaves. He comments that "yet animals are more high-minded, since no lion ever enslaved itself to another lion, nor a horse to another horse, for lack of courage." (pg 24). He has a great line that could apply to 'o how the mighty are fallen' or 'he puts his shoes on one at a time just like everyone else' but much more vivid: "The heart and life of a great and triumphant emperor are but the breakfast of a little worm." (pg 25).

One amazing bit of information in this text is when Montaigne is enumerating various ways in which animals seem to have powers of reason (not just good instincts). He refers to dogs which guide the blind and describes several observed instances asking "How could anyone have made that dog understand that it was its task to consider only the safety of its master and to neglect its own comfort in order to serve him? And how did it know that a certain road would be quite broad enough for it, but would not be so for a blind man? Can all this be understood without ratiocination and without thought?" (pg 26)

"It is one and the same nature that runs its course. If anyone had judged well enough of the present state, he could certainly infer from this both the whole of the future and the whole of the past." (pg 29).

Though Montaigne professes admiration for many of animals' qualities, his interpretation of some observations and stories is still quite anthropomorphic. He describes the story of the philosopher Thales' mule who stumbled while carrying a load of salt across the river. Realizing that its load was now lighter (because some of the salt has melted) the mule made it a practice to put its load under water. Montaigne describes this as malice and the mule as having malicious subtlety. It seems to be to be intelligence and figuring out a cause and effect relationship which is how we think animals primarily learn - admittedly a difficult cause and effect relationship because there would be a lag time between the action and the effect but research is currently being done showing some animals to be capable of episodic memory.

"As to war, which is the greatest and most solemn of human actions, I would like to know if we want to use it as an argument for some prerogative, or, on the contrary, as evidence of our imbecility and imperfection; as indeed our knowledge of how to defeat and slaughter one another, to ruin and destroy our own species, seems to have little attraction for the beats who do not have it." (pg 35)

"The souls of Emperors and of cobblers are cast in the same hold." (pg 38)

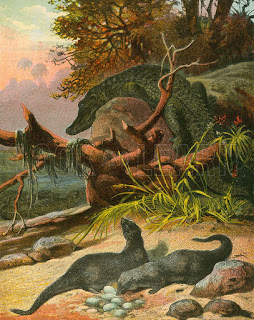

Montaigne mentions the ichneumon a couple of times. This is an african mongoose reputed to attack or control crocodiles by stealing and eating its eggs.

|

| Ichneumons and Crocodile |

|

| Ichneumon |

3. MAN'S KNOWLEDGE CANNOT MAKE HIM HAPPY

"If man were wise, he would fix the true price of each thing according to its greatest utility and fitness for his life." (pg 49)

"It is only humility and submission that can produce a good man." Montaigne says that man "must not be allowed o choose [his duty] according to his reasoning; others according to the imbecility and infinite variety of our arguments and opinions, we would finally forge for ourselves duties that would set us to eating one another..." (pg49). He adds that the 1st law God gave man was "a law of pure obedience". "[...] every sin arises from being opinionated." "The 1st temptation that came to human nature from the side of the devil, his 1st poison, was insinuated in us through the promises he made us of knowledge and awareness." "Man's plague is the belief that he has knowledge." (pg 50)

"That is why ignorance is so highly recommended by our religion as appropriate for belief and obedience."

Montaigne says that there is general agreement among philosophers that "the sovereign good consists in tranquility of soul and body."

Epictetus says that "man has nothing uniquely his own except the use of his opinions".

"We have to be made into animals to become wise and dazzled in order to be guided" (pg. 54)

He quotes Ecclesiastes 1:18 "In much wisdom there is much grief; and he who increases knowledge, increases travail and sorrow." (pg 57)

and Seneca "Does it please you? Bear it. Does it not please you? Get out of it however you can."

4. MAN'S KNOWLEDGE CANNOT MAKE HIM GOOD

"How can reason and intelligence, of which we make use in order to move from the obscure to the clear, [belong to God], seeing there is nothing obscure to God?" (pg 61)

Montaigne quotes Aristotle saying "He is capable neither of favour nor anger, since where such passions are, they are all weaknesses." (pg 61)

Montaigne "[...] Our faith is not our own acquisition; it is a pure gift of another's liberality."

saying that it's not through our reason or our intellect that we receive our religion.

5. MAN HAS NO KNOWLEDGE

In which Montaigne tries to answer whether man's search for knowledge over the centuries has enriched him or provided any "solid truth". The main benefit has been to recognize man's weakness.

"This largest part of what we know is the smallest part of the things we do not know." or "Even what we think we know is a piece, and a very small piece, of our ignorance." (pg 62)

Anyone seeking knowledge comes to one of 3 conclusions (pg 63):

- he has found it

- he cannot find it

- he is still looking for it

"Anyone who imagines a perpetual confession of ignorance [...] will understand Pyrrhonism."

Montaigne is dismissive and even very negative about curiosity, about knowledge simply for knowledge's sake, mentioning Eudoxus who wanted some day to see the sun close up, even if "he would be at once burned up by it." He wants to acquire knowledge that will result, in the act of its acquisition, in his losing not only that knowledge but all his past and future knowledge. (pg 73).

He speaks about ancient philosophers having found an "occupation fitting for the natural curiosity in us." (pg 73)

On pg 76, Montaigne lists numerous thinkers and briefly sums up their beliefs or philosophy about God. He wonders why mankind has wanted to put human qualities and foibles onto God or their gods. "Man would have done better [...] to take to himself the conditions of divinity and to bring those conditions down here rather than to send up there his corruption and his wretchedness." (pg 79)

He speaks of Mohammed who "promises his people a carpeted paradise paved with gold and jewels, peopled with girls of great beauty, with wines and rare food, I see clearly that they are mockers who are catering to our stupidity to sweeten and attract us by these opinions and hopes, suited to our mortal appetite." This comment reminds me of visits I have had from Jehovah's Witnesses proseletyzing at my front door and thinking to convince me of the attractions of paradise by showing me cheap coloured cartoons of a version of the Garden of Eden, and telling me earnestly that this is where I could end up if I convert, pointing at the picture as if it was a glossy brochure from some time-share in Cancun.

"We want to enslave God to the vain and feeble appearance of our understanding, him who has made both us and our knowledge." (pg 85)

And he writes about the presumption of assuming that what God has wrought on Earth is the sum total of all his ideas and creations, "the sum of the whole of everything" as Lucretius said, VI 679-80