Michel de Montaigne was born in 1533, into an aristocratic family at the chateau de Montaigne near Bordeaux. His mother was from a wealthy, originally Iberian, Jewish family. The children were all raised Catholic though some of Montaigne's siblings later became Protestant. His father was given a book by Raymond Sebond titled Natural Theology. Montaigne mentions that "the novelties of Luther were beginning to gain favour and to shake our traditional belief in many places." Sebond was a Spanish medical doctor practicing in Toulouse two hundred years earlier and his book was a defense of Catholicism against atheists. Montaigne translated the book into French for his father and it was published. Montaigne comments that he felt he should write the Apology (pg 2) "Since many people take pleasure in reading him - and especially the ladies, to whom we have to give particular assistance [...]"

FIRST OBJECTION AGAINST SEBOND, AND MONTAIGNE'S REPLY

Montaigne felt that radical scepticism of the Pyrrhonian variety is the proper intellectual attitude. Question everything. I liked the motto of the epechistes "I hold back" (meaning I withhold judgement) Good motto to have (and one Marcus Aurelius took very much to heart).

It is thought that all our seeming knowledge arises from our 5 senses.

Montaigne felt that belief comes from enlightenment from God. He thought that if this were not the case, then all the ancient wise people "would not have failed to arrive at that knowledge in their reasoning." pg 3 He is not blind to the many issues associated with religion including Catholicism and he discusses them in his book.

pg 5 "God owes his extraordinary aid to faith and religion, not to our passions.."

pg 5 "People are the leaders here and make use of religion. It ought to be quite the contrary."

pg 6 " We burn people who say that truth must suffer the yoke of our necessity."

pg 6 " I see clearly now that we willingly assign to devotion only the religious duties that flatter our passions."

pg. 6 "There is no hostility so extreme as that of the Christian. Our zeal works marvels when it seconds our inclination towards hatred, cruelty, ambition, greed, slander, and rebellion. On the other hand, it neither walks nor flies toward goodness, benevolence, temperance, if some rare complexion does not miraculously predispose it to them." "Our religion is meant to eradicate vices; it covers them, nourishes them, and encourages them."

Montaigne quotes Lucretius and Diogenes as he notes that if we truly believed in the blessings of heaven then why are we afraid of death, something I've always wondered about when being educated about Heaven or preached to about heaven.

He writes about people believing in religion through fear and those who find religion only when they are at risk of dying, in mortal terror. "A nice faith that believes what it believes only because it lacks the courage to disbelieve it." pg 8

In his 1st apology, Montaigne goes on to say that it's not credible that God has not left his mark somewhere in the world. He says that Sebond "shows us how there is no part of the world that disclaims its maker." pg 9 He ends by quoting Horace saying "If you have something better, produce it, or accept our rule."

SECOND OBJECTION AGAINST SEBOND, AND MONTAIGNE'S REPLY

In his reply to peoples' 2nd objection to Sebond, Montaigne says that his approach will be to "crush and trample underfoot human vanity and pride; to make them feel the inanity, the vanity and nothingness of man; to snatch from their hands the miserable weapons of their reason; to make them bow their heads and bite the dust beneath the authority and reverence of divine majesty." pg 11

He quotes many philosophers (Herodotus, the apostles Peter and James, Plato - he LOVES to quote) but to me they are just statements not proof and certainly not compelling. He also quotes St. Augustine who railed against the injustice of denying the truth of something on the basis that our reason has not been up to the challenge of proving it. This has more power for me but it still doesn't make articles of faith true (which I realize is somewhat of an oxymoronic statement on my part but makes a bit more sense if you are an unbeliever).

1. THE VANITY OF MAN'S KNOWLEDGE WITHOUT GOD

Montaigne goes on to examine man if there was no God and refers to man's dominion over everything asking "Is it possible to imagine anything so ridiculous as that this wretched and cowardly creature, who is not even master of himself, exposed to threats from all things, should call himself master and emperor of the universe when he lacks the power to understand its least part, let alone to command it?" (pg 12) Here is where Montaigne would have lost me had we been arguing this because I don't believe (nor do I think the majority believe in this day and age) that 'man' has dominion over the universe - though I would be hard-pressed to prove this seeing what we are doing to the environment and our hubris in genetic engineering (not because we are treading on God's territory but because I do believe in the inevitable 'rightness' [though that's not the correct word] of natural selection much more than I believe in human understanding or wisdom).

Part of his argument revolves around the power of the celestial bodies, the heavens to regulate men's lives and it's difficult for me to follow this argument, not having any knowledge of the state of astrology or cosmology at the time. I know that it was an active area and can easily look up that Copernicus published his work in 1543 and Galileo didn't publish until 1642 but other than this vague awareness, I'm ignorant of what was being thought and discussed at the time. There is a governing aspect to how he seems to consider the celestial sphere that I don't understand.

He quotes Seneca, writing "Among other inconveniences of mortality Is the darkness of the understanding , not so much the need to make errors as the love of errors."

2. MAN IS NO BETTER THAN THE BEASTS

Montaigne speaks about man being stuck in the worst part of the universe and in the "worst condition of the 3 kinds of animals" (i.e.: aerial, aquatic and terrestrial). He calls man presumptuous for putting himself above other animals, separating himself from other animals. "By what comparison between them and us does he infer the stupidity he attributes to them?" He says "When I play with my cat, who knows if she is making more of a pastime of me than I of her?" This thought has been the basis of many a joke and Gary Larson Far Side cartoon. Very pertinently Montaigne asks about animals "The same defect that prevents communication between them and us, why is it not as much our fault as theirs?" (pg 15).

He notes that "we discover quite plainly that there is full and complete communication between them and they understand one another, not only within the same species, but also across different species," and quotes Lucretius "And the cattle lacking speech, and even the wild beasts, make themselves understood with different and varied cries according as they feel fear, pain, or joy." If Lucretius understood in the 1st or 2nd century BCE that animals feel fear and pain, and Montaigne in the 16th c. AD quotes this, how does Descartes consider that animals were mechanistic (as our class discussion last night seemed to say) and how were vivisectionists up until only a few decades ago able to claim that animals don't feel pain as humans do? Montaigne lists off various aspects in which animals exceed humans in their ability and knowledge of the natural world and he comments "[...] their brutal stupidity surpasses, in all circumstances, everything that our divine invention and our arts can do." Montaigne quotes Lucretius again saying "Everything develops according to its own character, and all keep the differences that the fixed laws of nature have established between them" (pg 22) but he doesn't [yet] give us his thoughts on the laws of nature and what they are, where they come from and are they fixed? Montaigne speaks about whether man alone has imagination, if "this unruliness in his thoughts, representing to himself what is, what is not, and what he wishes - the false and the true - this is an advantage that has been dearly bought, giving him little to boast about. For from it flows the principal source of the evils that beset him: sin, illness, irresolution, affliction, and despair." (pg 22).

Montaigne says - and I don't know where the support for this statement comes from - "It is more honourable, and closer to divinity, to be guided and required to act in an ordered way by a natural and inevitable condition, rather than to act in that way through a presumptuous and fortuitous freedom."

Montaigne refers to differences between how we treat animals and says we also treat people differently, then referring to treatment of servants and slaves. He comments that "yet animals are more high-minded, since no lion ever enslaved itself to another lion, nor a horse to another horse, for lack of courage." (pg 24). He has a great line that could apply to 'o how the mighty are fallen' or 'he puts his shoes on one at a time just like everyone else' but much more vivid: "The heart and life of a great and triumphant emperor are but the breakfast of a little worm." (pg 25).

One amazing bit of information in this text is when Montaigne is enumerating various ways in which animals seem to have powers of reason (not just good instincts). He refers to dogs which guide the blind and describes several observed instances asking "How could anyone have made that dog understand that it was its task to consider only the safety of its master and to neglect its own comfort in order to serve him? And how did it know that a certain road would be quite broad enough for it, but would not be so for a blind man? Can all this be understood without ratiocination and without thought?" (pg 26)

"It is one and the same nature that runs its course. If anyone had judged well enough of the present state, he could certainly infer from this both the whole of the future and the whole of the past." (pg 29).

Though Montaigne professes admiration for many of animals' qualities, his interpretation of some observations and stories is still quite anthropomorphic. He describes the story of the philosopher Thales' mule who stumbled while carrying a load of salt across the river. Realizing that its load was now lighter (because some of the salt has melted) the mule made it a practice to put its load under water. Montaigne describes this as malice and the mule as having malicious subtlety. It seems to be to be intelligence and figuring out a cause and effect relationship which is how we think animals primarily learn - admittedly a difficult cause and effect relationship because there would be a lag time between the action and the effect but research is currently being done showing some animals to be capable of episodic memory.

"As to war, which is the greatest and most solemn of human actions, I would like to know if we want to use it as an argument for some prerogative, or, on the contrary, as evidence of our imbecility and imperfection; as indeed our knowledge of how to defeat and slaughter one another, to ruin and destroy our own species, seems to have little attraction for the beats who do not have it." (pg 35)

"The souls of Emperors and of cobblers are cast in the same hold." (pg 38)

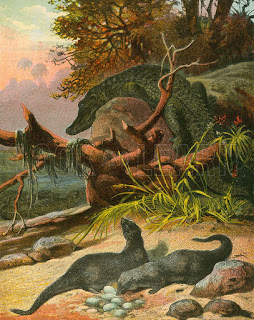

Montaigne mentions the ichneumon a couple of times. This is an african mongoose reputed to attack or control crocodiles by stealing and eating its eggs.

|

| Ichneumons and Crocodile |

|

| Ichneumon |

3. MAN'S KNOWLEDGE CANNOT MAKE HIM HAPPY

"If man were wise, he would fix the true price of each thing according to its greatest utility and fitness for his life." (pg 49)

"It is only humility and submission that can produce a good man." Montaigne says that man "must not be allowed o choose [his duty] according to his reasoning; others according to the imbecility and infinite variety of our arguments and opinions, we would finally forge for ourselves duties that would set us to eating one another..." (pg49). He adds that the 1st law God gave man was "a law of pure obedience". "[...] every sin arises from being opinionated." "The 1st temptation that came to human nature from the side of the devil, his 1st poison, was insinuated in us through the promises he made us of knowledge and awareness." "Man's plague is the belief that he has knowledge." (pg 50)

"That is why ignorance is so highly recommended by our religion as appropriate for belief and obedience."

Montaigne says that there is general agreement among philosophers that "the sovereign good consists in tranquility of soul and body."

Epictetus says that "man has nothing uniquely his own except the use of his opinions".

"We have to be made into animals to become wise and dazzled in order to be guided" (pg. 54)

He quotes Ecclesiastes 1:18 "In much wisdom there is much grief; and he who increases knowledge, increases travail and sorrow." (pg 57)

and Seneca "Does it please you? Bear it. Does it not please you? Get out of it however you can."

4. MAN'S KNOWLEDGE CANNOT MAKE HIM GOOD

"How can reason and intelligence, of which we make use in order to move from the obscure to the clear, [belong to God], seeing there is nothing obscure to God?" (pg 61)

Montaigne quotes Aristotle saying "He is capable neither of favour nor anger, since where such passions are, they are all weaknesses." (pg 61)

Montaigne "[...] Our faith is not our own acquisition; it is a pure gift of another's liberality."

saying that it's not through our reason or our intellect that we receive our religion.

5. MAN HAS NO KNOWLEDGE

In which Montaigne tries to answer whether man's search for knowledge over the centuries has enriched him or provided any "solid truth". The main benefit has been to recognize man's weakness.

"This largest part of what we know is the smallest part of the things we do not know." or "Even what we think we know is a piece, and a very small piece, of our ignorance." (pg 62)

Anyone seeking knowledge comes to one of 3 conclusions (pg 63):

- he has found it

- he cannot find it

- he is still looking for it

"Anyone who imagines a perpetual confession of ignorance [...] will understand Pyrrhonism."

Montaigne is dismissive and even very negative about curiosity, about knowledge simply for knowledge's sake, mentioning Eudoxus who wanted some day to see the sun close up, even if "he would be at once burned up by it." He wants to acquire knowledge that will result, in the act of its acquisition, in his losing not only that knowledge but all his past and future knowledge. (pg 73).

He speaks about ancient philosophers having found an "occupation fitting for the natural curiosity in us." (pg 73)

On pg 76, Montaigne lists numerous thinkers and briefly sums up their beliefs or philosophy about God. He wonders why mankind has wanted to put human qualities and foibles onto God or their gods. "Man would have done better [...] to take to himself the conditions of divinity and to bring those conditions down here rather than to send up there his corruption and his wretchedness." (pg 79)

He speaks of Mohammed who "promises his people a carpeted paradise paved with gold and jewels, peopled with girls of great beauty, with wines and rare food, I see clearly that they are mockers who are catering to our stupidity to sweeten and attract us by these opinions and hopes, suited to our mortal appetite." This comment reminds me of visits I have had from Jehovah's Witnesses proseletyzing at my front door and thinking to convince me of the attractions of paradise by showing me cheap coloured cartoons of a version of the Garden of Eden, and telling me earnestly that this is where I could end up if I convert, pointing at the picture as if it was a glossy brochure from some time-share in Cancun.

"We want to enslave God to the vain and feeble appearance of our understanding, him who has made both us and our knowledge." (pg 85)

And he writes about the presumption of assuming that what God has wrought on Earth is the sum total of all his ideas and creations, "the sum of the whole of everything" as Lucretius said, VI 679-80

On pg 87 Montaigne gets into discussing hybrid and ambiguous forms between human and brute nature and describes "countries where men are born without heads, carrying their eyes and mouth on their chest" - I don't know where this came from - it reminds me of the section in Lucretius where he lists off all the fantabulous creatures in other parts of the world or in days past. I have a real problem with this section. Montaigne lists these bizarre forms of humans (with one eye on forehead, who are without a mouth and nourish themselves via odours etc) and then immediately goes on to say that if this is the case, "how many of our descriptions are false? Man can no longer laugh nor perchance be capable of reason and of society. The governance and the cause of our internal structure would be for the most part irrelevant." (pg 87). I don't see this as a logical conclusion to the presence (or possibility) of humans with different characteristics.

Montaigne writes about the practice for philosopher's of looking to the natural world for truth: "For to go according to nature, for us, is only to go according to our intelligence, insofar as we can follow ad insofar as we can see into it. What is beyond is monstrous and disordered." (pg 87). He mentions Euripides and quotes Stobaeus, "Who knows if what we call dying is not living, as living is dying." Montaigne says that our life is an infinitesimal mote in an infinity of time and writes that "death occupies all that is beyond and all that is before this moment and a good part of this moment as well." (pg 88).

He has a great paragraph (pg 88) briefly summarizing various philosophers' philosophies in one sentence. He has structured it well so that each summary either contradicts itself internally and/or contradicts the one before or after it, ending the list of course by saying "that even the one is not, and that there is nothing."

It's about how I'm feeling about all these ideas right now.

Montaigne then gets into a discussion about the limitations of language and again, this is something that is resonating with me right now because I am getting bogged down in definitions and in my lack of knowledge of scholastic terminology. We are reading 2 texts a week (and a couple of weeks 4 texts) and there isn't the time to do much research for context, background, much less the academic underpinnings.

Montaigne says "God cannot do everything; for God cannot kill himself when he wants to, which is the greatest privilege we have in our condition." "God has no power over the past except forgetfulness." (pg 89) "Our presumptuousness wants to pass divinity through our sieve." (pg 90)

He also writes about the presumptuousness of mankind to think that God cares more about or involves himself more in those things that are important to us. I've always felt this way about prayer, such as when you would hear about someone praying to win a football game or a big contract (why would God care and if He did care, why would he care more about you than about the other contenders), similarly when you would read about a devout king praying for success on the battlefield - why would God grant him success but allow defeat to the other side (assuming the same religion) or regardless of who wins, allow all the carnage and destruction of the battle itself? It never made sense to me (among oh so many other things admittedly). As Montaigne puts it His hand "extends to all things in the same way [...] our interest has nothing to do with it [...]" (pg 90)

I have trouble with the sentence "Nature wants like relations in like things." Says who? I agree that in the last century the concept of equilibrium seemed to hold true in many cases (physics, medicine, chemistry) with Newton's Law of Reciprocal Actions and the chemical reactions that occur constantly in our bodies to keep everything in equilibrium (acid-base, the colloid osmotic pressure within our circulation, the ion movements keeping our cells functioning etc). But where is Montaigne's proof of this statement. This is where my lack of context and knowledge about the state of scientific knowledge at the time becomes a major problem. There may have been some very strong proofs at the time about some theories of equilibrium - I don't know if Montaigne is basing his statement on something like that or on some empirical knowledge from observation of the natural world.

Montaigne considers that our souls are "free and separated from the body" when we sleep and they can divine or prognosticate and "see things they would not know how to see if they were mixed with bodies." (pg 91)

When speaking about how our imaginations can cause many/all of our problems, he quotes Lucan "What they have made, they fear" and Pliny "Who is unhappier than a man whom his fictions govern?" (pg 91).

He quotes Xenophanes who had said that animals probably create a God in their own image just as man does and then refers to a gosling saying "All parts of the universe concern me; the earth serves me for walking, the sun to give me light [...]; there is nothing that that vault looks on as favourably as it does me; I am the beloved of nature [...]" (pg. 94). He does not think much of how mankind has imbued their divinities with very base human traits and assumed the gods to be preoccupied with unimportant minutiae (having a god to cure horses and one to make grapes grow, one in charge of trade etc) - and Montaigne lists off reams of various gods that have been described over the ages.

Montaigne says (about mankind's ability to know anything) "I will leave here more ignorant of everything except my ignorance". (pg 98) He says that "the reason we scarcely doubt about things is that we never test common impressions" (pg 101) He goes through, again, various philosophers' ideas on how the universe is constructed ("the atoms of Epicurus, the fullness and void of Lucretius and Democritus, that water of Thales [...] the fire of Heraclitus") saying for Aristotle, why make a negative such as privation part of the cause and origin of everything. (pg 101). He warns about the practice of believing experts in other fields and relying on their principles or practices.

"Every human presupposition and pronouncement has as much authority as every other if it is only reason that makes the difference." (pg 102)

Montaigne goes on to discuss what human reason has taught us about itself and the soul. The soul is likely just one entity (not one for each body part) and "through its faculties, reasons, remembers, understands, judges, desires [...] - and it is located in the brain." (pg 108). He sets out various philosophers' ideas about the soul/mind - body connection and again quotes Lucretius: "The mind must be bodily in nature, since it suffers from the stroke of bodily weapons." (pg111). He says we own any truth to luck and circumstance and that our reason "does not have the power to take advantage of [truth]. All things produced by our own reasoning and competence, the true as much as the false, are subject to uncertainty and debate." (pg 115).

"lose ourselves in that vast and troubled sea of medical errors" (pg 118)

"Our mind is a wandering, dangerous, and foolhardy utensil; it is difficult to join to it any order or measure." (pg 120)

6. MAN'S CLAIMS TO KNOWLEDGE ARE DEFECTIVE

7. THE SENSES ARE INADEQUATE

8. CHANGING MAN CANNOT KNOW CHANGING OR UNCHANGING THINGS

"But what is it, then, that truly is." (pg 163)

"God, who alone is" (pg 163)

"He fills eternity with a single now" - the Penguin Edition

No comments:

Post a Comment